Dismantling the Global Hegemonic Structure of Hierarchy within Academia

Over the past seven weeks, we have discussed various issues around studying Africa and debates within the field of African studies. Scholars are calling for epistemological freedom, decolonisation of the field, and to break the cycle of western dominance. This essay will argue that the hierarchical system within African studies is a manifestation of a larger global hegemonic power structure. Additionally, it will be argued that historians can play a crucial role in decolonising the field because of two things: First, a historical perspective sheds light on the intricacies and damaging nature of the structure which limits African epistemological freedom, increasing awareness. Second, historical research on non-colonial African history can contribute to changing the narrative of Africans solely as helpless victims of colonialism and reducing African history to colonial rule. This essay will support these claims by; showing the ways the historical hegemonic power structure is being kept in place; contextualising prominent debates in African studies within the global structure; exploring academic decolonisation efforts, and the historian’s role this process; and reflecting on ways to study the global structure as a subject matter. Lastly, I will reflect on my own positionality within African studies as a European historian.

The Global Hegemonic Structure

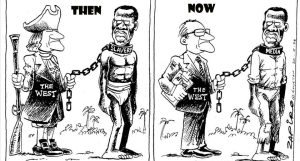

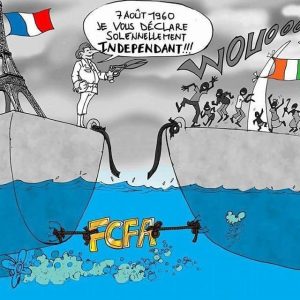

Through years of colonial occupation, systemic oppression, and exploitation of African populations and resources, a hegemonic, hierarchical global power structure has been created that continues to benefit western countries and disadvantage African countries.[1] One example of this is France’s continuous influence over the CFA, created by them in 1945. This currency, used by Central and West African countries, is still printed in France. The country also remains the holder of Central African Countries’ exchange reserves.[2] This limits these countries in their ability to control their own economies and upholds the structure of dependency.

Another example of the continuation of colonial structures is the assumption of western superiority and external conceptualisation of Africa as inferior. This belief was used to justify colonial governments and their actions during their rule.[3] Nowadays, this narrative continues to be spread through crisis thinking in the media. Crisis thinking perpetuates a single-sided narrative of an Africa in constant crisis. Africans are unable to deal with them, and western countries are more knowledgeable and skilled to help them.[4] This narrative perpetuates the assumption of western superiority and spreads it within western populations.[5]

Cartoon 1 depicting the continuation of colonial patterns.

Cartoon 2 depicting the continuation of colonial patterns.

Manifestations in the Academic World

In the academic world the structure of hierarchy manifests itself in various ways. Firstly, decisions made during colonial rule still impact the academic world today. The academic structure in Africa, including universities themselves, is based on western models. This established a dominant epistemological order that shaped western and African analyses.[6] Aspects like western theories and languages, like the use of terms such as empire and kingdom, may not reflect African realities.[7] This shows how systems created then still have impact today. Another example is the use of languages imposed by colonial governments. Different languages convey meaning in different ways, as they are the vessel through which knowledge is produced. The continuing use of these languages (in the academic sphere) restricts ways of knowledge production which might only be accessible through African languages.[8]

The second way the hegemonic world order manifests itself within academics is how the decision-making power still lies in the west. American and European academic centres hold money to fund research and the most prestigious journals in the field are situated there.[9] For African scholars to get published in these journals they need to prioritise what the journals deem important. This allows western academic centres to continue to decide what topics are researched and their priorities are valued, instead of scholars within Africa.[10] As De Ycaza stated, western knowledge systems continue to dominate African academia while the influence of Africa on western scholarship remains limited.[11]

Breaking Free from the Global Order

African authors have advocated for the decolonialisation of the field of African studies to achieve epistemological freedom. They emphasize that knowledge production must take place within Africa.[12] The next part of this essay will discuss ways to alter the structure, as well as historians’ role in the process of decolonising African studies.

An important contribution historians can make is changing the narrative of Africans as helpless victims of colonialism. By researching in the field of Afrikology, for example. Afrikology is a philosophy of knowledge production based on the recognition of the achievements of ancient African civilisation.[13] By highlighting these aspects of African history, a more holistic, multi-faceted view of Africa can be created. Nabudere has contextualised Afrikology as an antidote to Eurocentric thought, and philosophies like this are an important tool to decolonise the field.[14] Principles of Afrikology should be incorporated in history curriculums worldwide to change dominant assumptions of Africa. The spread of more holistic historical narratives should especially be aimed at young students to break the cycle of the single-sided narrative.

Another tool that can help scholars in decolonising the field is digital media. It has the ability to alter the standard assumptions around knowledge production, as argued by Mbembe. Through new media cultural boundaries can be transcended and African ways of knowing can take up space within new parameters of knowledge.[15] Victoria Bernal is not as positive about digital media. She points out that platforms of new media are in the hands of western powers, and that technical developments may create new concentrations of power faster than decolonial projects can dismantle established hierarchies.[16] Nevertheless, new media can still be a tool for academic decolonisation. It facilitates access to digitised sources and African ways of knowing, which is valuable for historians aiming to use African perspectives and non-traditional sources. Not only can digital media aid in the research itself, but it also allows for the spread and publication of African scholars’ work outside western boundaries.[17]

For researchers in the west, De Ycaza calls for self-reflection and humility, and the support of African scholarship to increase their significance and shift the academic centre.[18] As Ngaté has said, decolonised knowledge should address the needs of African societies.[19] However, some authors argue that scholars from the West should not study Africa, and that it is a form of cultural imperialism.[20] It can be, when it disregards African voices and perpetuates hegemonic power relations. However, preventing people from entering the academic field defeats the point of African studies as an interdisciplinary subject where multiple perspectives can enrich the field. Many authors have therefore suggested genuine collaboration between western and African academics.[21] Involving young students in this process can alter their assumptions of Africa and make them more attuned to African priorities and ways of knowing.[22] When studying Africa researchers and academic institutions from the west have a duty to listen to, collaborate with, and emphasize the priorities of African scholars and institutions.

Studying the Structure

Now that the global structure has been identified, and ways of decolonising the field discussed, I will mention some aspects that must be kept in mind when studying the global order as a subject. Doing so is important, as it creates understanding of damaging historical processes. Important considerations when researching are the language that is used and the narrative that it creates.

One term that has been questioned is the use of ‘decolonisation’ by Oluf́eṃ́i Taíẃò. He argues that by using the term one remains stuck in the past, unable to look forward and detangle from colonial legacies, and that diminishes the agency of African people.[23] For example, scholars have explained African countries’ post-independence government policies as continuing relations of colonial dependency in postcolonial contexts. Scholars might investigate other motivations of these policies to shed more light on the agency of African leaders, according to Taíẃò.[24] I do not entirely agree with Taíẃò, as I believe colonial patterns continue in the present, however it can be argued that the term colonialism has become a fashionable word. It is imperative that historians do not automatically resort to blaming colonialism to break from the one-sided narrative of Africa. Viewpoints like his are crucial to the field, as they force researchers to be critical, think outside the box, and stay on their toes, which is where researchers should be.

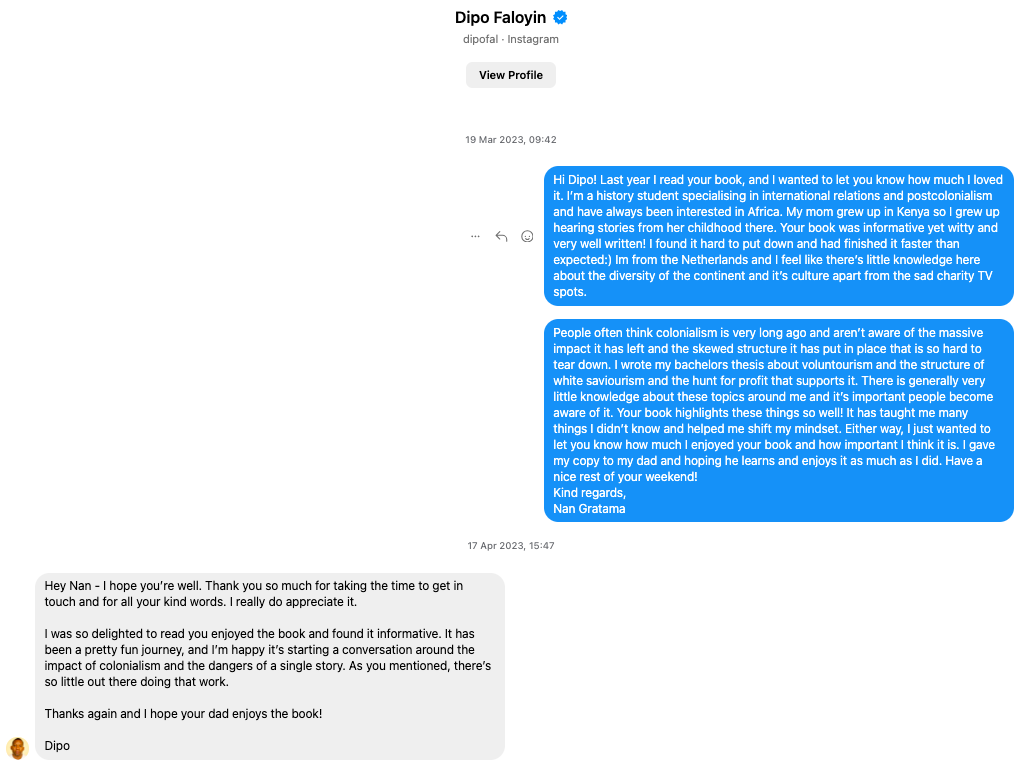

Although he does not agree with Taíẃò, Dipo Fayolin also emphasizes the dangers of a single story. In his book Africa is not a Country he aims to explain the effect of colonial oppression and how its legacies still affect Africa. He describes the phenomenon of crisis thinking and the narrative that is painted about Africa by the west.[25] Researchers need to make sure their research does not tell a single sided story and perpetuate damaging assumptions.

Conclusion

When choosing which master’s degree I wanted to pursue, I knew my interest lay in studying Africa. When considering the African studies master, I grappled with the question of whether it was my place, as a white European, to study or have an opinion about African matters. I choose to study colonial and global history instead. Upon reflection on the literature in this course, I have realised that there is indeed a lot of influence from the west on African studies and come to understand the need to decolonise the field. However, I also have come to understand that researchers from the west who are interested in Africa can play a role in shifting power dynamics by advocating for African voices, collaboration, and ensuring African priorities are valued. There is also a specific role for historians from the West, as they can create a counter narrative to the single-sided story perpetuated by crisis thinking. They can emphasize African agency their research, collaborate with African scholars, increase understanding of the continuation of damaging colonial patterns, and stay critical. This is why there should be an increased emphasis on the duty of Western scholars and institutions to use their position of power to mobilise the academic decolonisation effort. Nonetheless, a global structure is not dismantled in a day, and the difficulties in overthrowing epistemological norms and shifting power relations must not be underestimated.

Interaction I had with Dipo Fayolin earlier this year about the global hegemonic structure created by colonialism.

Bibliography

[1] Polly Pallister-Wilkins, ‘Saving the Souls of White Folk: Humanitarianism as White Supremacy’, Security Dialogue 52, no. 1 (1 November 2021): 98–106, https://doi.org/10.1177/09670106211024419

[2] Landry Signé, “How the France-Backed African CFA Franc Works as an Enabler and Barrier to Development,” Brookings Institution, December 7, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-the-france-backed-african-cfa-franc-works-as-an-enabler-and-barrier-to-development/.

[3] Pallister-Wilkins, ‘Saving the Souls of White Folk’, 98–106. ; Iris Berger, South Africa in World History, The New Oxford World History (Oxford ; Oxford University Press, 2009), 22-38, http://site.ebrary.com/id/10288340.

[4] Carla De Ycaza, “Competing Methods for Teaching and Researching Africa: Interdisciplinarity and the Field of African Studies,” Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies 38, no. 3 (2015), 71-72, https://doi.org/10.5070/f7383027721.

[5] Symen A. Brouwers, ‘The Positive Role of Culture: What Cross-Cultural Psychology Has to Offer to Developmental Aid Effectiveness Research’, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 49, no. 4 (1 May 2018): 519–34, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117723530

[6] Maria Grosz-Ngaté, “Knowledge and Power: Perspectives on the Production and Decolonization of African/Ist Knowledges,” African Studies Review 63, no. 4 (December 2020): 691–693, https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2020.102.

[7] Grosz-Ngaté, Knowledge and power, 696.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid, 709-710.

[11] De Ycaza, Competing Methods for Teaching and Researching Africa.

[12] Ibid ; Grosz-Ngaté, Knowledge and power. ; Geschiere, Dazzled by New Media.

[13] U. Chinedu Amaefula, “Sanya Osha. Dani Nabudere’s Afrikology: A Quest for African Holism. ,” African Studies Review 64, no. 1 (February 22, 2021): E46–48, https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2020.114.

[14] Amaefula, Dani Nabudere’s Afrikology, 46.

[15] Geschiere, Dazzled by New Media.

[16] Victoria Bernal, “Digitality and Decolonization: A Response to Achille Mbembe,” African Studies Review 64, no. 1 (March 2021): 41–56, https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2020.90.

[17] Geschiere, Dazzled by New Media.

[18] Grosz-Ngaté, Knowledge and Power.

[19] Ibid.

[20] De Ycaza, Competing Methods for Teaching and Researching Africa, 69.

[21] De Ycaza, Competing Methods for Teaching and Researching Africa.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Táíwò Olúfẹ́mi, “Introduction,” in Against Decolonisation: Taking African Agency Seriously (Hurst Publishers, 2022), 13–67.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Dipo Fayolin, “The Birth of White Saviour Imagery or How Not to Be a White Saviour While Still Making a Difference,” in Africa Is Not a Country: Breaking Stereotypes of Modern Africa (Penguin Random House UK, 2022), 20–67.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.