Assignment 1 — Léo and Vera

Decolonisation of Representation

Decolonisation of Representation

Introduction:

Over the latter half of the 20th Century, the world became accustomed to independent African states. We as Europeans assumed that our past had been fossilised; we no longer needed to feel present guilt for our political dominion over African peoples. By our own writings (Thornton 1963, 12), we had righted our ancestor’s wrongs. But our perspectives were flawed. Where our politicians (reluctantly) offered independence, African activists yelled that it only freed the political sphere, muddied by political assassinations and propping despotic dictatorships. Where Europe claimed economic autonomy, Africa outcried dependency and Structural Adjustment Programs. Where European museums justified protection of art, Africans saw theft, infantilization, and othering. Where European universities claimed freedom of thought, African scholars struggled to decolonise their minds and language (wa Thiong’o 1986, 6-9), alienated from their culture. Whether overtly or subconsciously, we Europeans separated ourselves from colonialism’s nefarious and sinister dominations, believing that political emancipation was sufficient.

Over the latter half of the 20th Century, the world became accustomed to independent African states. We as Europeans assumed that our past had been fossilised; we no longer needed to feel present guilt for our political dominion over African peoples. By our own writings (Thornton 1963, 12), we had righted our ancestor’s wrongs. But our perspectives were flawed. Where our politicians (reluctantly) offered independence, African activists yelled that it only freed the political sphere, muddied by political assassinations and propping despotic dictatorships. Where Europe claimed economic autonomy, Africa outcried dependency and Structural Adjustment Programs. Where European museums justified protection of art, Africans saw theft, infantilization, and othering. Where European universities claimed freedom of thought, African scholars struggled to decolonise their minds and language (wa Thiong’o 1986, 6-9), alienated from their culture. Whether overtly or subconsciously, we Europeans separated ourselves from colonialism’s nefarious and sinister dominations, believing that political emancipation was sufficient.

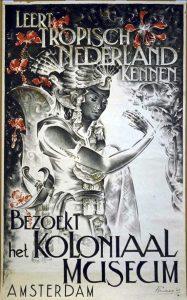

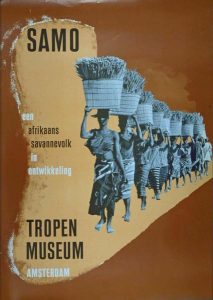

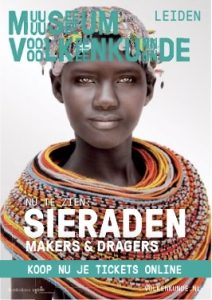

In academia, the transparency of this sinister nature has become accepted. To discuss colonialism is to discuss all of its elements. However, this is not the case outside of academia, particularly amongst the European public. When part of the cultures that imposed colonialism and the globalist order over 5 centuries, it requires effort and self-awareness to understand how colonialism not only hampered agency of thinking. To recognise the self-reproducing dominating representations of Africa(ns) in Europe, one needs look no further than Museum media in the Netherlands. The representations from the Tropen and Volkenkunde museums have been pivotal in maintaining the public’s perception of African artistry as crude and traditional.

elements. However, this is not the case outside of academia, particularly amongst the European public. When part of the cultures that imposed colonialism and the globalist order over 5 centuries, it requires effort and self-awareness to understand how colonialism not only hampered agency of thinking. To recognise the self-reproducing dominating representations of Africa(ns) in Europe, one needs look no further than Museum media in the Netherlands. The representations from the Tropen and Volkenkunde museums have been pivotal in maintaining the public’s perception of African artistry as crude and traditional.

Agency:

Western representations of Africans have – for many centuries – limited them to an ‘Other’. As the images in the sections below showcase, the limited celebration of African cultures’ diversity and growth plays a role in maintaining Africans as an Other, as noted by Smith’s review of Douglas & Poletti’s Life Narratives and Youth Culture: Representation, Agency, and Participation.

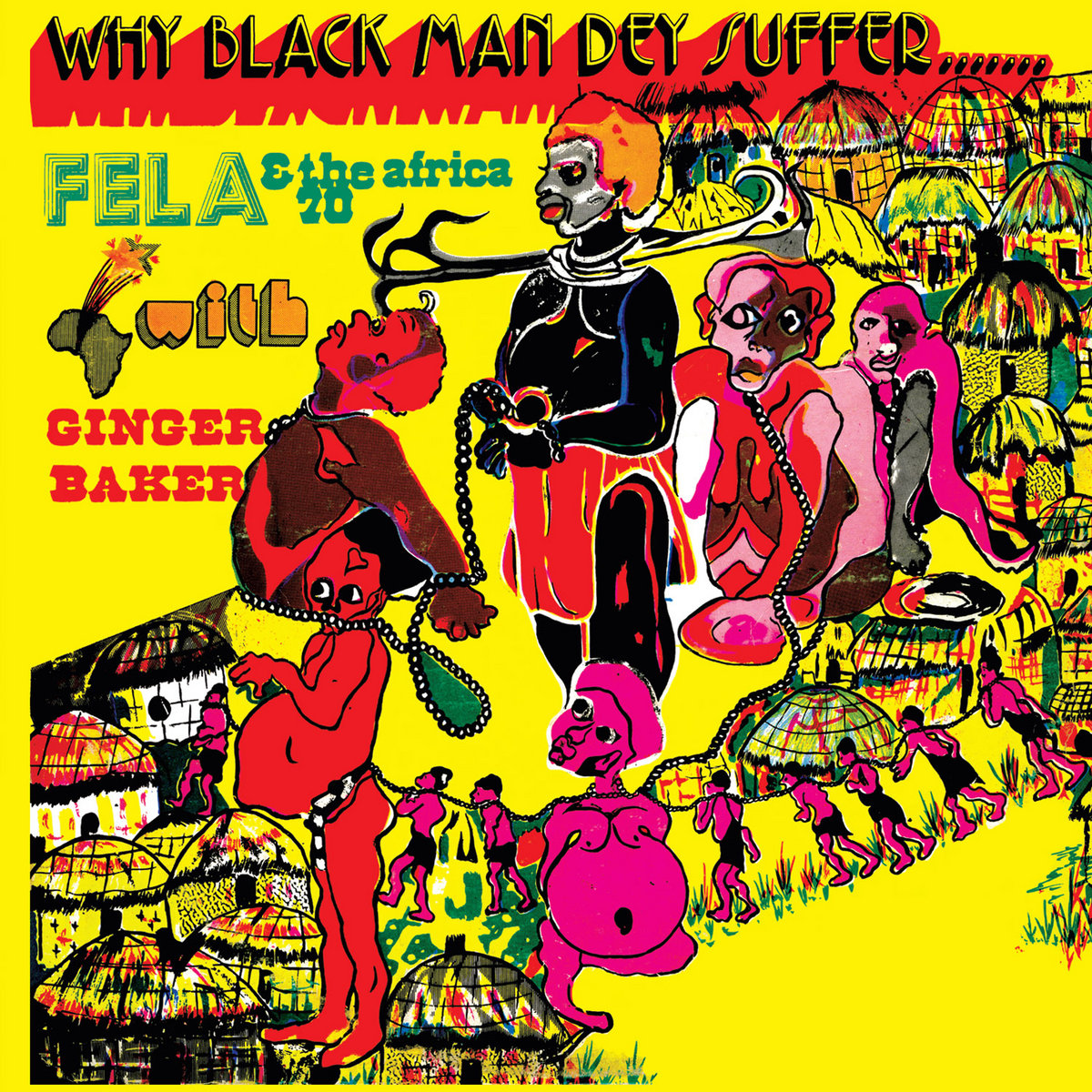

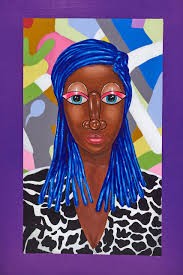

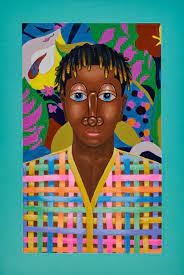

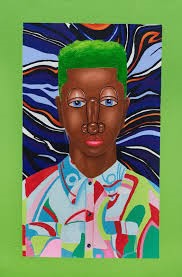

African agency through representation is most strongly exemplified by the reclamation of colour in mediatic imagery. The colourful nature and flamboyant fashion of Africa’s diverse culture has often been limited – if not ignored – in Western depictions, quieting its ‘Loudness’. Samson Bakare’s paintings sharply contrast this, highlighting Africa’s ongoing artistic ‘renaissance’. While much of this renaissance’s international popularity  emerged through musical artists (Afrobeat, Burna Boy, Lil Simz), there is an unquestionable visual art movement planting its feet.

emerged through musical artists (Afrobeat, Burna Boy, Lil Simz), there is an unquestionable visual art movement planting its feet.

No matter which of his paintings you put in focus, Bakare’s works scream independence and uniqueness. The beautiful depictions of noses stand in powerful opposition to many traditional depictions: not limited through the Western tradition of life-like and ‘refined’, but larger-than-life and almost poetic. Moreover, as a Nigerian artist, the beautiful implementation of background designs are symbiotic to the unique fashion patterns central to Nigerian culture. There is loudness, organised chaos, a fusion of independent elements to make something more. Agency emerges, as these subjects are free to depict themselves as something unseen in traditional representations. They create a niche for themselves. When compared to this, the Western Museum depictions of Africans appear bleak, depressed, and empty.

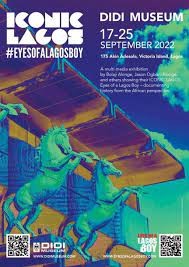

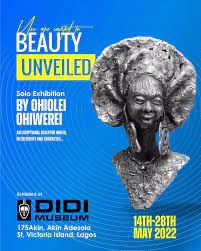

Looking further at African museums, such as the Didi Museum, this reclamation of agency is solidified. The subject is not the African person, nor their history, but what it means to be African. The fusion of brutal urbanisation with a colourful outlook on life. The subject is never tangible: simply the potential of the creators themselves. The ArtAfrica cover uses the silhouette of a black woman, but fills that silhouette with the quintessential artistic elements that have become synonymous with Africa’s diverse cultures. And once more, when compared to their European counterpart’s depictions, they seem void of life, essentialising, and simplistic. To claim agency is to reinvent oneself when they have been Othered. By refusing the given space, and claiming one’s own, African artists and museums can no longer be limited. They have their own niche, unique across the globe. And by cementing this niche, they exist by and for themselves to recreate, free of the trapping ideals of what an African should look like.

Colour Analysis:

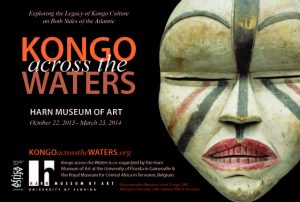

Compared to the examples above, There is a clear distinction between African museum posters and exhibitions in the West. Here, the Kongo Across the Waters exhibition uses the earthy browns-oranges, linking African cultures to the earth, nature, and an overall simplistic representation of Africa. Darkness and black colouring features heavily in Western representations of Africa. Binyavanga Wainaina in his text How to Write About Africa points out the constant usage of “Darkness” (Wainaina 2005,1) to describe Africa, similar to what Achille Mbembe described in his text Time on the Move: Africa “can only be understood through a negative interpretation” (Mbembe 2001, 1). The West was founded and maintained on whiteness and the self-associated ideals of ‘purity’. Africa, as its thematic and essentialised opposite, is thus routinely represented as this dark or black continent.

Compared to the examples above, There is a clear distinction between African museum posters and exhibitions in the West. Here, the Kongo Across the Waters exhibition uses the earthy browns-oranges, linking African cultures to the earth, nature, and an overall simplistic representation of Africa. Darkness and black colouring features heavily in Western representations of Africa. Binyavanga Wainaina in his text How to Write About Africa points out the constant usage of “Darkness” (Wainaina 2005,1) to describe Africa, similar to what Achille Mbembe described in his text Time on the Move: Africa “can only be understood through a negative interpretation” (Mbembe 2001, 1). The West was founded and maintained on whiteness and the self-associated ideals of ‘purity’. Africa, as its thematic and essentialised opposite, is thus routinely represented as this dark or black continent.

As can be seen above, muted browns, yellows, oranges and black are dominant. Brown is loosely associated with dirt and the earth. Yellows and oranges are seen as commonly used in “African” artworks and we see black as the mysterious, intimidating and heavy hue. The use of this colour scheme in posters and advertisements enforce popular essentialistic ways of thinking about Africa and Africans. We perceive a completely different message from the shades that Samson Bakara uses. No muddy, silencing tones. Bright, in-your-face, inclusive; these colours convey to the spectator that there is hope, luck, joy, and abundance.

Language Analysis:

Titles on museum posters in the Dutch public areas have in common their objective and academic use of language. There is not much imagination, inspiration or emotion expressed that may engage a potential visitor. Let’s look at some other examples of the use of language that stand out in these advertisements.

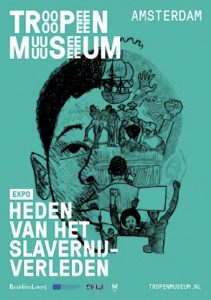

Poster 1 – “Present of the Slavery Past”

A loaded topic is wrapped in a dry, factual phrase. Emotion, anger, resentment are not part of the outward campaign. Of course, the modern-day implication of the slavery past is an important dimension to explore, but we could argue that a  museum can go further in trying to engage people with the content. This trend continues in Poster 2 – “Jewellery, makers and wearers”, where there is no linguistic depth to the campaign at first glance.

museum can go further in trying to engage people with the content. This trend continues in Poster 2 – “Jewellery, makers and wearers”, where there is no linguistic depth to the campaign at first glance.

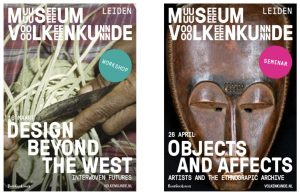

Furthermore displaying a theoretical and uninspiring title for a seminar is Poster 4 – Objects and Affects, Artists and the Ethnographic Archive. African culture is portrayed as archival and something to be studied rather than experienced, creating a distance between the Dutch learner and the African creator. The notion of the aforementioned “Other” is reinforced. This is a parallel to be found within all posters: the spectator will remain as such. It enforces an outward-in narrative.

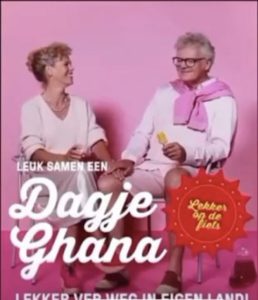

Poster 3: “Design Beyond the West”

A poster about intricate, century old, technical design methods is reduced to a practice that is “not the West”. The West here is central to the poster about a topic that has no ties to it. The desire to determine the West’s position within any matter showcases the level of linguistic colonisation still present in the Dutch offline public space.

General conclusion:

General conclusion:

The main takeaway from this blogpost is to consider how Western perceptions and representations of Africa, even if sometimes produced by a diaspora, differs so vastly from the African-made material. In the vast majority of cases, we see Western representers centre the African as the subject usually in relation to archaic ideals. However, in Africa we see a removal of the individual or past as the subject, and a centralising of Africa’s cultures and unique features beyond skin colour or colonial past. To the curious reader of this post: Challenge yourself by juxtaposing our Dutch and our African material to see what other differences or similarities you can find and leave it in a comment. Be sure to explore how these representations exist in your home country!

Bibliography:

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.