Decolonising the mind? – Where to look.

The ongoing debate of current African studies as well as the wider world is the concept of decolonising the mind. While for many Westerners the idea that African states gained independence decades ago and that was the end of it, the truth is evident across an array of social levels. Three personal and two prominent examples sprung to mind while thinking about modern-day colonialism.

On my way to the train this morning I was standing on the busy tram for the six-minute ride to Hollands Spoor. Sitting next to me was a North African woman wearing a hijab and talking on the phone. The middle-aged white woman in front of her turned around and gave an incredibly dirty look. It struck me once again how the disparity between cultures and races is still so pertinent, even in what would be considered an ethnically tolerant nation.

Growing up I went to a school in rural ‘white-picket-fence’ South England, about an hour away from London. The school was both day and boarding, with the boarders being either students from the local area but living outside of the catchment area, or ‘London Hong Kong and Nigerians’. Despite being born and raised in London for 8 years, my first realisation of systemic racism was when groups or ‘gangs’ of thirteen to eighteen-year-old Nigerian boys would be walking down the street, and the older members of the community would cross the street.

Now living and working in the Hague it is very apparent that some things that are considered ‘normal’ are anything from it. I work in a Belgian beer café on the Plein, called Leopold. The bar is (one would hope) ‘innocently’ named, however, every so often people ask me which Leopold of Belgium it was named after. While the correct answer is indeed Leopold the Second, known for his terrible deeds in the former Belgian Congo, it has become somewhat of an inside joke at work that if anybody asks, we reply “Definitely the first, the second would be a bit dicey”, or words to that effect.

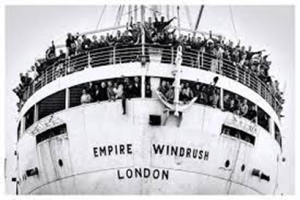

On a grander scale, one only has to look at the UK Government in order to understand the truly ingrained roots of this continued colonisation of minds and people. In the past, and recently having resurfaced, the government’s Windrush scandal is the perfect example. After World War Two, and due to a lack of workers, the Government passed the British Nationality Act of 1948, extending nationality to the colonies, and inviting them to live and work in Britain. The numbers vary from source to source, but thousands of people are believed to have come over in the two or so decades forming the Windrush generation. The majority of people came from the Caribbean, or, integrally reported their “last country of residence as somewhere in the Caribbean”, most deriving originally from Africa.

In 2018 the Windrush scandal brought to light the indecent treatment of the Windrush generation as it claimed that there was no record of who had been granted permanent stay in Britain due to the 1971 immigration act. This included things such as the government admitting to having “destroyed landing cards belonging to Windrush migrants in 2010”. This culminated in the threat of deportation for many who had arrived here as children.

An even more recent example of the British Government’s agenda is the proposed plan to divert all illegal immigrants and asylum seekers arriving at the borders to Rwanda, where a proposed deal, benefitting the Rwandan Government by hopefully contributing to the workforce (and additionally work as a deterrent against immigrants attempting to seek asylum in the United Kingdom). It could be argued that people often come for the freedoms and the opportunities offered by the prominent northern European country.

In summation, one only has to open one’s eyes to the reality around us that, unfortunately, many people can go through life without realising. Everybody grows up in their bubble of how life is, and many are oblivious to the still very neo-colonial world that we live in. Whether it is a conscious or subconscious metaphorical burying of the head in the sand, or indeed more malicious, is an individual thing.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.