Africa, the 21st Century, and Beyond

Africa has – for all its history – found itself in a unique situation compared to the rest of the world.

Despite numerous centuries of oppression and destructive exploitation, it has always bounced back to celebrate its richness and tenacity. Considering the demographic catastrophe that was the slave trade, Africa is currently on path to leading the world in population and population growth. No time is this bounce-back more apparent than in the 21st Century. Following a limited liberation in the latter half of the 20th Century, it now finds itself in a true age of agency, escaping beyond the Three C’s of representation by the West: Corruption, Conflict, and Crisis. Africa today is digital, diverse beyond generalisation, and with a growing academic richness that can no longer be downplayed. Hierarchies (of knowledge, power, equalities) will always persist, but they are now known and being chiselled. This critical essay will take central themes from the Researching Africa in the 21st Century course (Decolonisation, Agency, and Crisis Thinking) and utilise them in analysing the Three C’s of representation, and how it continues to damage Africa today.

Despite numerous centuries of oppression and destructive exploitation, it has always bounced back to celebrate its richness and tenacity. Considering the demographic catastrophe that was the slave trade, Africa is currently on path to leading the world in population and population growth. No time is this bounce-back more apparent than in the 21st Century. Following a limited liberation in the latter half of the 20th Century, it now finds itself in a true age of agency, escaping beyond the Three C’s of representation by the West: Corruption, Conflict, and Crisis. Africa today is digital, diverse beyond generalisation, and with a growing academic richness that can no longer be downplayed. Hierarchies (of knowledge, power, equalities) will always persist, but they are now known and being chiselled. This critical essay will take central themes from the Researching Africa in the 21st Century course (Decolonisation, Agency, and Crisis Thinking) and utilise them in analysing the Three C’s of representation, and how it continues to damage Africa today.

(De-)Colonialism:

Colonialism had an undeniable impact on Africa over the past half a millenia. When I analyse politics or anthropology, history often accompanies it hand in hand, for history raises the present as a parent raises a child. However, to reduce Africa to its relationship with colonialism would be to essentialise it beyond recognition. It has been central to the discourse of ‘What it means to be African’ but it also extends far beyond that. As such, Africa and colonialism exist as a double-edged sword: you cannot separate the two yet they must be separated. It is this dichotomy that makes Africa different from other colonised continents.

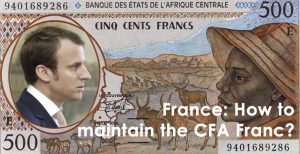

Decolonisation is no different, as it marked a turning point where African politique and states finally regained control over themselves, to be the driver in its own affairs. Particularly to the West, Africa as a whole could exist independently from Europe for the first time in centuries. However, one only needs to read African scholars (Táíwò, wa Thiong’o) to realise it is not so clear cut. The blogs of fellow African Studies academics Nan Gratama or Sweder Breet on France and the continued use of the CFA Franc illustrate this clearly: there are ongoing hegemonic structures that were founded and raised from colonial times. The existence of these has – as will be discussed below – concretely limited African agency. This is supported by wa Thiong’o in his famous book Decolonising the Mind. Here, wa Thiong’o accurately points out that much work by African scholars has been written in colonial language over indigenous ones. There is an inherent limitation of experience and culture when using a language over another and as such, African languages have been largely relegated out of the writing sphere. Quoting Gabriel Okara: “Living languages grow like living things, and English is far from a dead language.”[1] Okara is arguing that decolonisation extends beyond the political and can free the linguistic by claiming it for oneself, as many former English colonies have. But wa Thiong’o argues differently, that language and culture cannot exist without the other: language speaks what culture is, and culture creates language.[2] Furthermore, relative to subjugation, language was “the most important vehicle through which that power […] held the soul prisoner.”[3] By controlling language, one can control people. Or as stated by Cheikh Hamidou Kane: it was not the cannons of the first morning but the schools that followed.[4] Seeing all this – language as existence spoken, as an extension of colonial power, and the foundation of currencies on colonial relationships – decolonisation is not as clear cut as may be argued. It is a process in continuation, approaching its end of true decolonisation, if that is even possible.

This brings the discussion back to the Three Cs: Corruption, Crisis, and Conflict. Taking a Western Postcolonial lens, these Cs are caused by Africans, irrelevant of European views. But if we take an African Decolonial view, these Cs can be attributed to continued influence from the West. Can African economies be free to be considered corrupt and ‘underdeveloped’ if there is ongoing exploitation and pillaging by multinational corporations? Can states be unstable and internally violent if there are an amalgamation of ethnicities diverse beyond Western comprehension? Nigerian author Michael Nwankpa noted this, and argued that the British colonial government traded in violence so regularly that it served as the template for the post-independence government.[5] Similarly, the prioritisation of the Hausa-Fulani North of Nigeria as the political elite cemented their dominance over the political system. Thus, it is clear that while there has been a decolonial effort across Africa, it is still far from being Postcolonial; that is moving beyond the influence of colonialism. There is still very much an ongoing struggle to establish true independence. Nowhere is this more true than the aforementioned CFA Franc: a colonial relic currency still printed by France and tied to the  Euro, with barriers to direct trading between the colonial Francs. This relationship truly speaks on France and Africa. France still considers itself, geopolitically and socially, as the caretaker of Africa. Whether the Mali intervention, management of the Francs, political affairs interference, or French people’s blasé and ad hoc blame of the Three Cs on Africans ‘being that way’, the colonial influence remains strong across many spheres.

Euro, with barriers to direct trading between the colonial Francs. This relationship truly speaks on France and Africa. France still considers itself, geopolitically and socially, as the caretaker of Africa. Whether the Mali intervention, management of the Francs, political affairs interference, or French people’s blasé and ad hoc blame of the Three Cs on Africans ‘being that way’, the colonial influence remains strong across many spheres.

Agency:

Arguably the most interesting concept when navigating Africa and its dynamics with the world is agency. Whether colonialism & agency denial, decolonisation & agency revival, or even post-colonialism & Táíwò’s discourse on agency, African agency has been the subject of enormous discourse and disagreement. Firstly, what is agency? It largely emerged from the ideas of Anthony Giddens relating the individual to the structure. Unlike other early sociologists (Weber, Marx, etc.), Giddens recentered the focus on the individual, away from the structure and collective.[6] Furthermore, his agency is the rejection of neo-structuralism imposed on African societies and actors as being powerless for change due to their voicelessness.[7] To Giddens, agency can materialise in infinite ways beyond the traditional ways of power and impact. In the simplest terms, agency is the ability for an individual to exist and act in a structured society.

Taking Africa today, despite featuring only decolonised states, this discussion is still subject to much debate as was showcased above. When you see the CFA, the permanence of colonial languages, the relics of colonial governments as contemporary African states, or even the designation of African academics as subordinate by Western academia, one questions how much agency is available to African individuals. However, this can be overly reductive, as illustrated by Táíwò.

Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò is a Nigerian scholar who currently offers an opposition to decolonisation as defined by other African scholars. While he agreed with wa Thiong’o’s presentation of decolonisation as an effort beyond the political sphere, Táíwò argues that extending decolonisation beyond the political liberation of state apparati is “fruitless”.[8] He believes that there was an emancipation of the political and economy in terms of direction, but not inherently “control.”[9] Moreover, he defines what wa Thiong’o has spoken of as “Decolonisation2” – cultural, political, intellectual, social and linguistic elements are all to some degree artefacts of the colonial past.[10] While he has been critiqued for his potentially narrow definition of decolonisation,[11] he defends his position by stating there are as many variants of decolonisation as there are thinkers to promote it.[12] Later in his text,

Táíwò reiterates that the ultimate issue with decolonial discourse is its “oft-unappreciated failure to take seriously the complexity of African agency” and how it tackled colonialism.[13] This is what centralises Táíwò in the agency debate. The way wa Thiong’o has defined colonialism, it is the struggle to liberate the mind; a struggle to literate all the spheres from colonialism. But to Táíwò, this crushes agency as it limits Africans for being subjects to colonialism’s influences, rather than how Africans tinkered with those influences to create something more. What Nwankpa delegated to a legacy of colonial government leading to political violence, Táíwò would argue that violence is the agency of African politics.

Táíwò reiterates that the ultimate issue with decolonial discourse is its “oft-unappreciated failure to take seriously the complexity of African agency” and how it tackled colonialism.[13] This is what centralises Táíwò in the agency debate. The way wa Thiong’o has defined colonialism, it is the struggle to liberate the mind; a struggle to literate all the spheres from colonialism. But to Táíwò, this crushes agency as it limits Africans for being subjects to colonialism’s influences, rather than how Africans tinkered with those influences to create something more. What Nwankpa delegated to a legacy of colonial government leading to political violence, Táíwò would argue that violence is the agency of African politics.

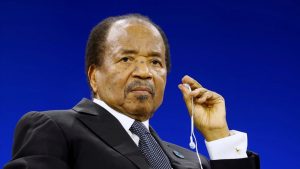

Similarly, the maintenance of African despots for 30 years is, to Táíwò, a decision that Africans are free to make. This is what stands out the most to me, that Africans are truly free to conduct their politics, states, economies, education, and linguistic choices as they see fit, rather than a longue durée symptom of a chronic colonial disease.

Similarly, the maintenance of African despots for 30 years is, to Táíwò, a decision that Africans are free to make. This is what stands out the most to me, that Africans are truly free to conduct their politics, states, economies, education, and linguistic choices as they see fit, rather than a longue durée symptom of a chronic colonial disease.

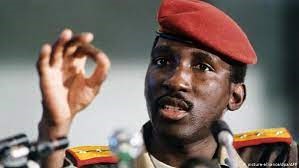

And thus re-emerges the Three Cs: Corruption, Crisis, and Conflict. In terms of agency, Táíwò would argue to his grave that these are true free actions of Africans. Even if colonial governments were beyond corrupt, incorporating rival ethnic groups and slapping borders that do not fit demographic lines amongst other criticisms, the contemporary result of conflict outbreak and political violence are within free Africans ability and right to do so, unlike what Nwankpa may argue. This is very much the vision that the West has, particularly citizens in the West and the representations they have grown accustomed to through media. While citizens do not speak for narratives, they undeniably shape them by continuing the discourse around it. It is clear there is a balancing act between on one hand the nefarious consequences of colonialism & neocolonialism covert control of the post-independence states, and on the other the unquestionable freedom and agency possessed by Africans. Is the election and maintenance of despots like Paul Biya a symptom of (neo-)colonialism, or a symptom of agency? Is the assassination of Thomas Sankara? It is clear that these imaginings and narratives of the Three Cs are far more complex than they present themselves. It is damaging, yet it must be respected in the same breath. What is most clear from Táíwò’s arguments, is that agency needs to be centred and not ignored, for Africans fought and earned a state that, at the end of the day, they alone have the right to influence, as well as self-fabricate a national culture.

The globalised world we live in today is one of hierarchies. Whether it be geopolitics, economics, academia, voice, agency, or influence, there are established hierarchies that set the global playing field. Africa has for too long been victim to these hierarchies, often perpetrated and reproduced by the powers that set the dynamics in place, and often at the expense of those below. Thus when considering this, alongside the ethics of these arrangements and the Three Cs, there is a great deal to reflect on. On the one hand, it is clear the influence of colonialism today is not negligible, it is in fact quite robust. African academia is practically universally written in colonial languages, as they are considered higher up the hierarchy. However, academia globally is largely written in English and other colonial languages. I believe this is what gives Táíwò’s arguments their greatest strengths. To define all that is holding Africa back as part of Decolonisation2 is overly reductive of the global situation we see today. In a globalised world, the idea of colonial power and colony doesn’t do justice to the core-periphery dynamic that runs that system. Is Africa decolonising, or is it merely a victim like the rest of the peripheral regions of a globalised hierarchical system. To reduce it to Decolonisation2 is to remove Africa’s agency to navigate this order, an order in which many of whom were not colonised the same way find themselves. Thus we return to the representation of Three Cs. This imagining, this media based creation, goes beyond understanding Africa under crisis thinking, and into the realm of Africa as a subordinate. Agency is removed from Africans and delegates that to ‘innate characteristics’, the foundations for systemised racism. In my view, contemporary Africa is all the aforementioned: it is equally a product of the interactions from colonial times, as it is free to utilise its agency to lead itself however – like much of the world – it only has as much agency as the globalised hierarchy allows.

Notes:

[1] Ngũgĩ wa thiongo, “The Language of African Literature,” in Decolonising the Mind: The politics of language in African Literature (1986), 9.

[2] Ibid, 8 & 16.

[3] Ibid, 9.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Michael Nwankpa, Nigeria’s Fourth Republic, 1999-2021 : A Militarised Democracy (Abingdon & New York: Routledge, 2023), 26-29.

[6] Marlie Van Rooyen, “Structure and Agency in News Translation: An Application of Anthony Giddens’s Structuration Theory,” Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 31, no. 4 (2013): 496.

[7] Mirjam de Bruijn and Sara de Wit, “The Debate on African Agency and Insecurity (Suffering and Smiling),” Researching Africa in the 21st Century (Lecture, Leiden University, October 23, 2023).

[8] Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò, Against Decolonisation : Taking African Agency Seriously, (London, England: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers Ltd., 2022), 3.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] James D. Sidaway, “Review of: Against Decolonisation: Taking African Agency Seriously . Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò . C. Hurst & Co (in Collaboration with the International African Institute), London, UK, 2022,” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 379.

[12] Táíwò, Against decolonisation, 50.

[13] Ibid, 183-84.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.